PhilAypee wrote: ⤴Mon Apr 13, 2020 5:37 pm

If you look on

YouTube you'll find a few

British programmes of

Tony Robinson walking some of those paths, mostly in

England.

ZakGordon wrote: ⤴Thu Apr 16, 2020 3:45 am

Cool! Thanks for the tip Phil, i do love me some Baldrick doing history

This

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/ar ... nloads.cfm could be interpreted as a bit more on ‘Tony’s Travels’, or, ‘Bustling along with Baldric’, but doesn’t have to be.

The Botch.

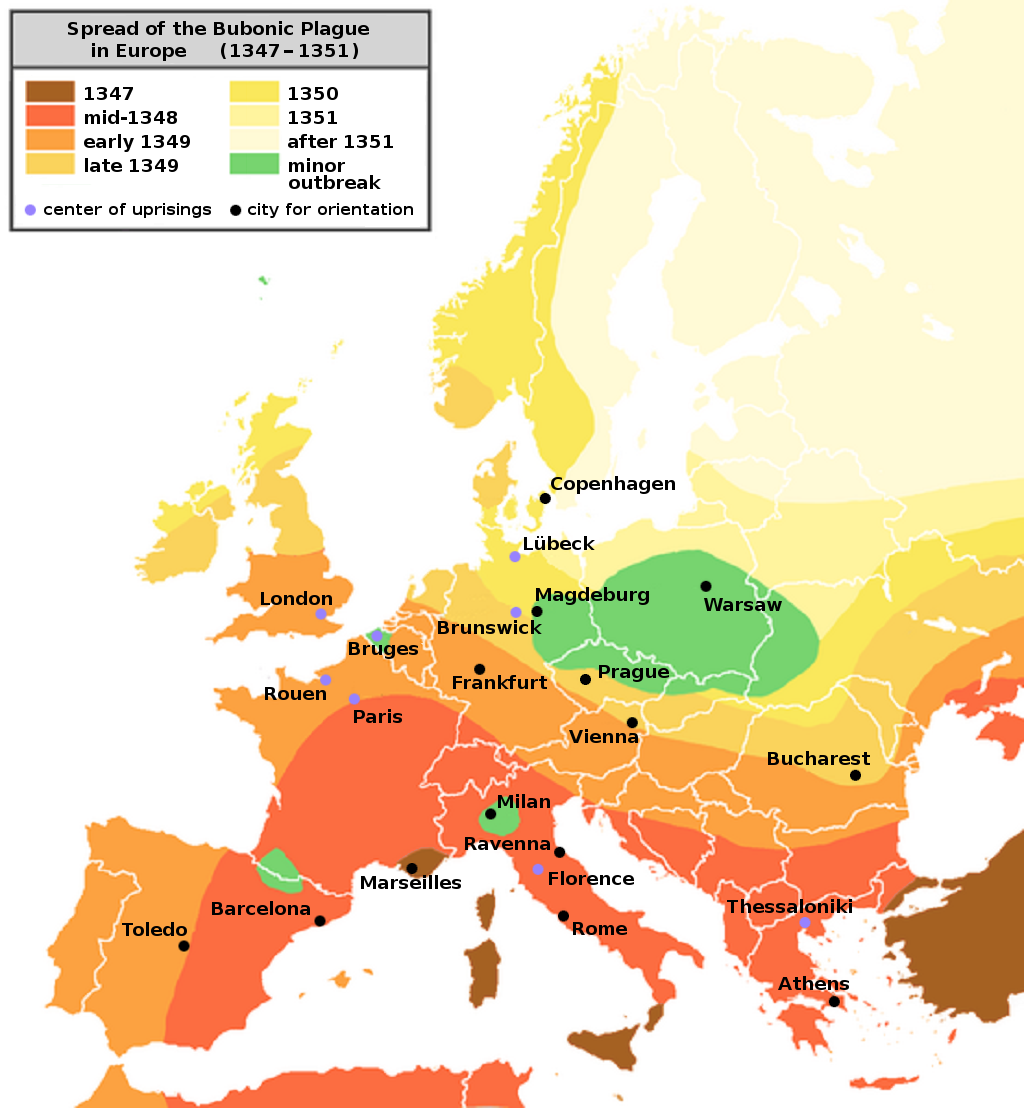

Europe was hit in 1347 and in June, July or August 1348 the Botch as we knew it, or the Great Mortality descended on England, probably arriving at Melcombe Regis, and hung around for up to two, maybe even three, years.

The dates on this may be a little off, but y’know,

William of Malmesbury said that it arrived in England, about the time of the Translation of St Thomas.

That’s about July 7th.

Possibly a little strangely, or perhaps ‘news’ travelled slowly, but on July 18 ‘48 Thomas de Chysenhale and Thomas Florak were appointed to arrest sufficient mariners from Dorset, Southampton and Devon, to man twelve ships arrested for the king's service in the port of Southampton.

But I’ve no idea why, or if it actually happened.

The first recorded death was the priest of West Chickerell in Sept ‘48. In W Dorset, between 17 Oct and 20 Nov, eight churches can be identified which lost their priests: Toller Porcorum, Litton Cheney, Askerswell, Maiden Newton, Hooke, Allington, Broad Windsor and Bradpole, which actually lost two in three months. Abbotsbury Abbey was the first monastery attacked as it’s abbot was dead before 3 Dec.

On the other side of the county, the prior of the ‘alien’* priory of Wareham had to be replaced and the king appointed a successor on 4 November. It’s also said that the Black Death appeared to have hit Wareham hard, with seven priests recorded as dying in 1348 alone – perhaps the priory was hit particularly badly. By 18 Nov the churches of Bridport, Tyneham, Lulworth, and Cerne were all ‘vacant’. A table of the churches for Dorset during this period shows that the mortality was at its highest between Nov and Feb. From 8 Oct ‘48 to Jan ‘49, the crown, appointed no less than thirty ‘livings’ in the diocese of Salisbury, the greater number of which belonged to Dorset.

* not English.

At first I thought that the abbot of Bindon, William de Comenore, may have escaped as on 19 Apr ‘48, To the mayor and bailiffs of Dover.

Order to permit the abbot of Bynedon in co. Dorset, who is about to set out to the Roman court, by the king's licence, for certain affairs concerning that abbey, to cross from that port with his moderate household and his reasonable expenses in gold, to the town of Caleys, provided that he make no apportum and take no gold or silver out of the realm beyond his said expenses.

However, in 1350 Bindon had a new abbot, as ‘Philip’ is recorded as such.

In most of the various ‘takes’ on the Black Death, the Isle of Purbeck seems to have escaped remarkably lightly. But on scouring the records, on Nov 27 1348, Presentation of Richard de Bery to the church of Corfe.

The incredibly important use of Purbeck marble went into decline c1350, being replaced by Alabaster. One day I was chatting with a senior employee of the local National Trust, and she wonders if the Black Death did actually have a large effect amongst those who ‘worked’. Pondering on that, I can imagine the: knights, lords and priests, grabbing their families and supplies and locking themselves in Corfe, whilst around them the plague raged.

The problem with that though is that there’s no evidence, but looking at it ‘behaviourally’, in Jan ‘49, Ralph of Shrewsbury, the bishop of Bath and Wells retired to his house at Wiveliscombe, near Taunton. Very kindly, he posted a letter to all the priests in his diocese saying that it was their ‘duty to provide for the salvation of souls’. About the poor and their final confessions, he said, 'If they are sick and on the point of death and cannot secure the services of a priest, they should make confession to each other and if no man is present then even to a woman'. GASP.

Bishop Ralph did not even venture as far as Yeovil until December 1349, when things were probably returning to normal.

This next bit is entirely ‘possible’, maybe ‘probable’, which doesn’t stop it being entirely horrible.

“Given that the mortality associated with the Black Death was extraordinarily high and selective, the medieval epidemic might have powerfully shaped patterns of health and demography in the surviving population, producing a post-Black Death population that differed in many significant ways, at least over the short term, from the population that existed just before the epidemic. By targeting frail people of all ages, and killing them by the hundreds of thousands within an extremely short period of time, the Black Death might have represented a strong force of natural selection and removed the weakest individuals on a very broad scale within Europe.”

All I'd say is that most elderly poor people could, by modern standards, have been frail, as they'd grown up during a time of general starvation, and the young may have been more susceptible anyway.

Before the Black Death, it’s reckoned that c15% of us died under 10. c30%, between 10 and 20. c35% between 20 and 40, leaving 20% of us to live beyond 40.

The figures do change after the Black Death, when childhood remained very dangerous as there was little change, but ‘only’ 20 to 22% of us died between 10 and 20, and ‘only’ about 20% between 20 and 40, leaving nearly 40% of us to age and wither. Um, grow old gracefully.

Life went on, but maybe not very peacefully, as in July ‘49, Robert Fitz Payn, Richard de Turbervill, chivaler, Robert Martyn, chivaler, John de Brudeport of Byre and John de Mundene were given a ‘Commission of the peace, in the county of Dorset.’

It was unusual to appoint six commissioners – was there a lot of peace that needed keeping? Or when so many people were dying do you appoint six commissioners when three or four would normally do?

Or were they all off to their second homes, as it appears that many wanted to leave England and on Nov 20 ‘48, To the sheriff of Kent.

Order to cause proclamation to be made that no earl, baron, knight, esquire or other man at arms, shall presume to cross out of England to parts beyond without the king's special order and licence, upon pain of forfeiture. By K.

The like to the following, to wit; The sheriff of Dorset and Somerset, Cornwall, Essex, Southampton, London, Surrey and Sussex, Devon, Norfolk and Suffolk, Lincoln.

Lock down. Oh, what does that remind me of?

John Matravers, son of John Matravers le piere, died in 1348 and so could have died of the Black Death, but in November ‘48 he was ‘going abroad on the king's service’, so he could have been involved in a shipwreck and drowned, or been killed by ‘wreckers’, of could have died doing some deed for his king, or picked up the Black Death in foreign climes – maybe in the Channel Islands where his father was ‘Governor’* - but possibly absent, or locked up in a castle as Edward III wrote to him that, “By reason of the mortality among the people and fishing folk of these islands, which here as elsewhere has been so great, our rent for the fishing, which has been yearly paid us, cannot be now obtained without the impoverishing and excessive oppression of those fishermen still left”.

EDIT * I just looked it up - he was appointed on July 16 '48. END OF EDIT.

“It’s thought that the Black Death was responsible for ending the long period of continuous habitation of Sark, around 1348”.

It’s said that, in Jersey, 8 out of the 10 parishes lost their priest. At Tournai, in densely populated Flanders, it was reported that, “no one, rich, middling or poor, was safe … and certainly there were many deaths among the parish priests and chaplains who heard confessions and administered the sacraments, and also among the parish clerks and those who visited the sick with them.”

In the chronicle of the Cistercian abbey of Louth Park (Lincolnshire), a monk said, “In the year of the Lord 1349 the hand of Almighty God struck the human race a deadly blow … This stroke felled Christians, Jews and infidels alike. It killed confessor and penitent together. In many places it did not leave a fifth of the people alive.”

When the Black Death abated isn’t precisely known, but the king obviously thought it was over by 8 Oct ‘49 as Martin de Ixnyng, clerk and controller of the work in the palace of Westminster and the Tower of London and Robert Esshyng, ‘mason’, were appointed to get stone from Purbyk, Porteland, Birelond*, ‘and elsewhere’. It was to be brought to London with ‘all speed’, and although implied in many earlier records, by the use of ‘arrest’, here there’s no doubt. Ixnyng and Esshyng were given the “power to imprison all persons found rebellious herein.”

By Mar 10 1350 it was probably over, or at least mainly over, as Robert de Essbyngg – oh, blinkin’ ‘ell – Esshyng or Essbyngg – the same person? Probably.

Sorry, one of them, was appointed of to take workmen and stonemasons to dig stones in the quarries of Abbotesbury and Wynesbache**, co. Dorset, and Bere, co. Devon, for some works in the palace of Westminster, and carriage for the stone to the sea; by view and testimony of the sheriffs of those counties, such workmen and carriage to be paid for out of the issues of the counties and indentures of the payments to be made between the sheriffs and Robert; and to have the stone brought thence by sea to the said palace.

Aaargh - medieval ‘red-tape’.

* Birelond. Probably Bere Ferrers in Devon. EDIT: IDIOT, no it isn't. MORON. End of edit.

** Wynesbache. Probably the now disused, Windsbatch Quarry, Upwey, nr Weymouth.

Although Melcombe Regis is probably rightly considered* as the most likely entry point of the Great Mortality, I wonder if S Dorset may, in general, also be guilty. There was trade at: Lyme, Bridport, Melcombe, Wareham and Poole, we had ‘pirates’ sailing up the Frome from Wareham and up the Stour from Christchurch - where there would have been pilgrims and trade as well.

*Unless you live somewhere else by the sea and are ‘scrawling-off’ a local history.

“The second visitation of the plague in 1361 was hardly less severe, the list of churches [needing priests] for the last six months of that year being especially heavy.”

“There were further outbreaks of the plague in Britain in 1381, 1390, 1405, and every few years until 1665, since when it has hardly returned to England.”

Possible evidence of the return in 1381/2,

The Abbess and convent of Shaftesbury to the King and council …. they are so ruined by pestilences among their tenants, which have killed almost all of them, by murrain among their cattle at various times in all their possessions, and by other charges which necessity forces them to bear from day to day, they will find it very hard to get to the end of the year without endangering themselves to their creditors …. It pleases the king that this petition be granted, on the advice of his council.

Assessment.

“The fourteenth-century pandemic accelerated this process of Schumpeterian 'creative destruction', by undermining the powers of lords and greater towns and by facilitating the development of more powerful states. Supported by social groups whose bargaining powers were strengthened by the shortage of labour and which stood to gain from lower feudal levies and weaker jurisdictional monopolies, aspiring rulers increased the jurisdictional integration of their territories and began incorporating new ones, made markets more competitive, stimulated commercialisation and set the stage for the long sixteenth-century boom.

…. Rising consumption is well attested for meat, cheese, butter, beer and, in Mediterranean countries, wine, olive oil, fruit and vegetables. (Some things never change.)

Probate inventories, dowries, and archaeological excavations indicate that consumption of cheap manufactures (cloth, crockery, wooden utensils) also increased significantly.

Evidence of increased commercialisation can be found in the growth across late medieval Europe of rural manufacture, particularly of cloth but also of crockery, glassware and pewter.

Evidence of product invention and innovation is harder to come by and has attracted less attention. Examples include the mass diffusion of linen underwear (whose effects for public health should not be underestimated), the invention of transportable hard cheese (caciocavallo and parmesan) in Italy, the development of herring and pilchard preservation in north-western Europe, the selection of higher quality wines identified by their place of origin, and the widespread diffusion of plants of Islamic origin (indigo, rice, spinach, sugar, artichokes, probably eggplants) that had been little more than garden curiosities before the Black Death.”

It’s also said that there was more road maintenance and that the growth of markets and fairs, including job fairs, show growth and choice.

More good news, Aug 28 1348, To the sheriff of Dorset for the time being.

Order every year to Sheen manor [some poorly scanned/copied words] to Richard Pupplington the king's Serjeant, one of the foresters of Purbyk forest, 6d a day for life; as the king is informed that he has served the late king and the king more than forty years, travailing in the late king's wars, and is one of the oldest archers of the crown, and that he has no means of living save by the king's service, wherefore the king has granted him 6d a day for life, as he had in the late king's time.

Richard was the first of quite a few, who were ‘pensioned off’ to look after the forest of Purbyk.

Should you read that Purbeck was a ‘warren’ - most of it was, but the king kept a bit as ‘forest’, within which his law was even more absolute than it was in the ‘warren’. In theory, if you were caught doing something in the ‘warren’, then normal law applied, but if you were caught in the ‘forest’, then your outlook wouldn’t have been too rosy.